Êíèãà: Phantoms in the Brain

CHAPTER 8 “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”

| <<< Íàçàä CHAPTER 7 The Sound of One Hand Clapping |

Âïåðåä >>> CHAPTER 9 God and the Limbic System |

CHAPTER 8

“The Unbearable Lightness of Being”

“One can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age I always did it for half an hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

“As a rule,” said Holmes, “the more bizarre a thing is the less mysterious it proves to be. It is your commonplace, featureless crimes which are really puzzling, just as a commonplace face is the most difficult to identify”.

I’ll never forget the frustration and despair in the voice at the other end of the telephone. The call came early one afternoon as I stood over my desk, riffling through papers looking for a misplaced letter, and it took me a few seconds to register what this man was saying. He introduced himself as a former diplomat from Venezuela whose son was suffering from a terrible, cruel delusion. Could I help?

“What sort of delusion?” I asked.

His reply and the emotional strain in his voice caught me by surprise. “My thirty-year-old son thinks that I am not his father, that I am an impostor. He says the same thing about his mother, that we are not his real parents.” He paused to let this sink in. “We just don’t know what to do or where to go for help. Your name was given to us by a psychiatrist in Boston. So far no one has been able to help us, to find a way to make Arthur better.” He was almost in tears. “Dr. Ramachandran, we love our son and would go to the ends of the earth to help him. Is there any way you could see him?”

“Of course, I’ll see him”, I said. “When can you bring him in?”

Two days later, Arthur came to our laboratory for the first time in what would turn into a yearlong study of his condition. He was a good-looking fellow, dressed in jeans, a white T-shirt and moccasins. In his mannerisms, he was shy and almost childlike, often whispering his answers to questions or looking wide-eyed at us.

Sometimes I could scarcely hear his voice over the background whir of air conditioners and computers.

The parents explained that Arthur had been in a near-fatal automobile accident while he was attending school in Santa Barbara. His head hit the windshield with such crushing force that he lay in a coma for three weeks, his survival by no means assured. But when he finally awoke and began intensive rehabilitative therapy, everyone’s hopes soared. Arthur gradually learned to talk and walk, recalled the past and seemed, to all outward appearances, to be back to normal. He just had this one incredible delusion about his parents — that they were impostors — and nothing could convince him otherwise.

After a brief conversation to warm things up and put Arthur at ease, I asked, “Arthur, who brought you to the hospital?”

“That guy in the waiting room”, Arthur replied. “He’s the old gentleman who’s been taking care of me.”

“You mean your father?”

“No, no, doctor. That guy isn’t my father. He just looks like him. He’s — what do you call it? — an impostor, I guess. But I don’t think he means any harm.”

“Arthur, why do you think he’s an impostor? What gives you that impression?”

He gave me a patient look — as if to say, how could I not see the obvious — and said, “Yes, he looks exactly like my father but he really isn’t. He’s a nice guy, doctor, but he certainly isn’t my father!”

“But, Arthur, why is this man pretending to be your father?”

Arthur seemed sad and resigned when he said, “That is what is so surprising, doctor. Why should anyone want to pretend to be my father?” He looked confused as he searched for a plausible explanation. “Maybe my real father employed him to take care of me, paid him some money so that he could pay my bills.”

Later, in my office, Arthur’s parents added another twist to the mystery. Apparently their son did not treat either of them as impostors when they spoke to him over the telephone. He only claimed they were impostors when they met and spoke face-to-face. This implied that Arthur did not have amnesia with regard to his parents and that he was not simply “crazy”. For, if that were true, why would he be normal when listening to them on the telephone and delusional regarding his parents’ identities only when he looked at them?

“It’s so upsetting”, Arthur’s father said. “He recognizes all sorts of people he knew in the past, including his college roommates, his best friend from childhood and his former girlfriends. He doesn’t say that any of them is an impostor. He seems to have some gripe against his mother and me.”

I felt deeply sorry for Arthur’s parents. We could probe their son’s brain and try to shed light on his condition — and perhaps comfort them with a logical explanation for his curious behavior — but there was scant hope for an effective treatment. This sort of neurological condition is usually permanent. But I was pleasandy surprised one Saturday morning when Arthur’s father called me, excited about an idea he’d gotten from watching a television program on phantom limbs in which I demonstrated that the brain can be tricked by simply using a mirror. “Dr. Ramachandran”, he said, “if you can trick a person into thinking that his paralyzed phantom can move again, why can’t we use a similar trick to help Arthur get rid of his delusion?”

Indeed, why not? The next day, Arthur’s father entered his son’s bedroom and announced cheerfully, “Arthur, guess what! That man you’ve been living with all these days is an impostor. He really isn’t your father. You were right all along. So I have sent him away to China. I am your real father.” He moved over to Arthur’s side and clapped him on the shoulder. “It’s good to see you, son!”

Arthur blinked hard at the news but seemed to accept it at face value. When he came to our laboratory the next day I said, “Who’s that man who brought you in today?”

“That’s my real father.”

“Who was taking care of you last week?”

“Oh”, said Arthur, “that guy has gone back to China. He looks similar to my father, but he’s gone now”.

When I spoke to Arthur’s father on the phone later that afternoon, he confirmed that Arthur now called him “Father”, but that Arthur still seemed to feel that something was amiss. “I think he accepts me intellectually, doctor, but not emotionally”, he said. “When I hug him, there’s no warmth.”

Alas, even this intellectual acceptance of his parents did not last. One week later Arthur reverted to his original delusion, claiming that the impostor had returned.

•

Arthur was suffering from Capgras’ delusion, one of the rarest and most colorful syndromes in neurology.1

The patient, who is often mentally quite lucid, comes to regard close acquaintances — usually his parents, children, spouse or siblings — as impostors. As Arthur said over and over, “That man looks identical to my father but he really isn’t my father. That woman who claims to be my mother? She’s lying. She looks just like my mom but it isn’t her.” Although such bizarre delusions can crop up in psychotic states, over a third of the documented cases of Capgras’ syndrome have occurred in conjunction with traumatic brain lesions, like the head injury that Arthur suffered in his automobile accident. This suggests to me that the syndrome has an organic basis. But because a majority of Capgras’ patients appear to develop this delusion “spontaneously”, they are usually dispatched to psychiatrists, who tend to favor a Freudian explanation of the disorder.

In this view, all of us so-called normal people as children are sexually attracted to our parents. Thus every male wants to make love to his mother and comes to regard his father as a sexual rival (Oedipus led the way), and every female has lifelong deep-seated sexual obsessions over her father (the Electra complex). Although these forbidden feelings become fully repressed by adulthood, they remain dormant, like deeply buried embers after a fire has been extinguished. Then, many psychiatrists argue, along comes a blow to the head (or some other unrecognized release mechanism) and the repressed sexuality toward a mother or father comes flaming to the surface. The patient finds himself suddenly and inexplicably sexually attracted to his parents and therefore says to himself, “My God! If this is my mother, how come I’m attracted to her?” Perhaps the only way he can preserve some semblance of sanity is to say to himself, “This must be some other, strange woman.” Likewise, “I could never feel this kind of sexual jealousy toward my real dad, so this man must be an impostor.”

This explanation is ingenious, as indeed most Freudian explanations are, but then I came across a Capgras’ patient who had similar delusions about his pet poodle: The Fifi before him was an impostor; the real Fifi was living in Brooklyn. In my view that case demolished the Freudian explanation for Capgras’ syndrome. There may be some latent bestiality in all of us, but I suspect this is not Arthur’s problem.

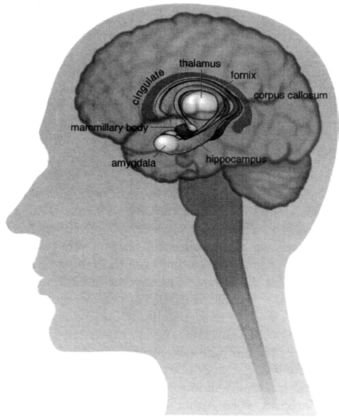

A better approach for studying Capgras’ syndrome involves taking a closer look at neuroanatomy, specifically at pathways concerned with visual recognition and emotions in the brain. Recall that the temporal lobes contain regions that specialize in face and object recognition (the what pathway described in Chapter 4). We know this because when specific portions of the what pathway are damaged, patients lose the ability to recognize faces,2 even those of close friends and relatives — as immortalized by Oliver Sacks in his book The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. In a normal brain, these face recognition areas (found on both sides of the brain) relay information to the limbic system, found deep in the middle of the brain, which then helps generate emotional responses to particular faces (Figure 8.1). I may feel love when I see my mother’s face, anger when I see the face of a boss or a sexual rival or deliberate indifference upon seeing the visage of a friend who has betrayed me and has not yet earned my forgiveness. In each instance, when I look at the face, my temporal cortex recognizes the image — mother, boss, friend — and passes on the information to my amygdala (a gateway to the limbic system) to discern the emotional significance of that face. When this activation is then relayed to the rest of my limbic system, I start experiencing the nuances of emotion — love, anger, disappointment — appropriate to that particular face. The actual sequence of events is undoubtedly much more complex, but this caricature captures the gist of it.

After thinking about Arthur’s symptoms, it occurred to me that his strange behavior might have resulted from a disconnection between these two areas (one concerned with recognition and the other with emotions).

Maybe Arthur’s face recognition pathway was still completely normal, and that was why he could identify everyone, including his mother and father, but the connections between this “face region” and his amygdala had been selectively damaged. If that were the case, Arthur would recognize his parents but would not experience any emotions when looking at their faces. He would not feel a “warm glow” when looking at his beloved mother, so when he sees her he says to himself, “If this is my mother, why doesn’t her presence make me feel like I’m with my mother?” Perhaps his only escape from this dilemma — the only sensible interpretation he could make given the peculiar disconnection between the two regions of his brain — is to assume that this woman merely resembles Mom. She must be an impostor.3

Figure 8.1 The limbic system is concerned with emotions. It consists of a number of nuclei (cell clusters) interconnected by long @-shaped fiber tracts. The amygdalain the front pole of the temporal lobereceives input from the sensory areas and sends messages to the rest of the limbic system to produce emotional arousal. Eventually, this activity cascades into the hypothalamus and from there to the autonomic nervous system, preparing the animal (or person) for action.

Now, this is an intriguing idea, but how does one go about testing it? As complex as the challenge seems, psychologists have found a rather simple way to measure emotional responses to faces, objects, scenes and events encountered in daily life. To understand how this works, you need to know something about the autonomic nervous system — a part of your brain that controls the involuntary, seemingly automatic activities of organs, blood vessels, glands and many other tissues in your body. When you are emotionally aroused — say, by a menacing or sexually alluring face — the information travels from your face recognition region to your limbic system and then to a tiny cluster of cells in the hypothalamus, a kind of command center for the autonomic nervous system. Nerve fibers extend from the hypothalamus to the heart, muscles and even other parts of the brain, helping to prepare your body to take appropriate action in response to that particular face. Whether you are going to fight, flee or mate, your blood pressure will rise and your heart will start beating faster to deliver more oxygen to your tissues. At the same time, you start sweating, not only to dissipate the heat building up in your muscles but to give your sweaty palms a better grip on a tree branch, a weapon or an enemy’s throat.

From the experimenter’s point of view, your sweaty palms are the most important aspect of your emotional response to the threatening face. The dampness of your hands is a sure giveaway of how you feel toward that person. Moreover, we can measure this reaction very easily by placing electrodes on your palm and recording changes in the electrical resistance of your skin. (Called the galvanic skin response or GSR, this simple little procedure forms the basis of the famous lie detector test. When you tell a fib, your palms sweat ever so slightly. Because damp skin has lower electrical resistance than dry skin, the electrodes respond and you are caught in the lie.) For our purposes, every time you look at your mother or father, believe it or not, your body begins to sweat imperceptibly and your galvanic skin response shoots up as expected.

So, what happens when Arthur looks at his mother or father? My hypothesis predicts that even though he sees them as resembling his parents (remember, the face recognition area of his brain is normal), he should not register a change in skin conductance. The disconnection in his brain will prevent his palms from sweating.

With the family’s permission, we began testing Arthur on a rainy winter day in our basement laboratory on campus. Arthur sat in a comfortable chair, joking about the weather and how he expected his father’s car to float away before we finished the morning’s experiments. Sipping hot tea to take the chill from his bones, Arthur gazed at a video screen saver while we affixed two electrodes to his left index finger. Any tiny increase in sweat on his finger would change his skin resistance and show up as a blip on the screen.

Next I showed him a sequence of photos of his mother, father and grandfather interleaved with pictures of strangers, and I compared his galvanic skin responses to that of six college undergraduates who were shown an identical sequence of photos and who served as controls for comparison. Before the experiment, subjects were told that they would be shown pictures of faces, some of which would be familiar and some unfamiliar. After the electrodes were attached, they were shown each photograph for two seconds with a fifteen- to twenty-five-second delay between pictures so skin conductance could return to baseline.

In the undergraduates, I found that there was a big jolt in the GSR in response to photos of their parents — as expected — but not to photos of strangers. In Arthur, on the other hand, the skin response was uniformly low.

There was no increased response to his parents, or at times there would be a tiny blip on the screen after a long delay, as if he were doing a double take. This result provided direct proof that our theory was correct.

Clearly Arthur was not responding emotionally to his parents, and this may be what led to the loss of his galvanic skin response.

But how could we be sure that Arthur was even seeing the faces? Maybe his head injury had damaged the cells in the temporal lobes that would help him distinguish between faces, resulting in a flat GSR whether he looks at his mother or at a stranger. This seemed unlikely, however, since he readily acknowledged that the people who took him to the hospital — his mother and father — looked like his parents. He also had no difficulty in recognizing the faces of famous people like Bill Clinton and Albert Einstein. Still, we needed to test his recognition abilities more direcdy.

To obtain direct proof, I did the obvious thing. I showed Arthur sixteen pairs of photographs of strangers, each pair consisting of either two slightly different pictures of the same person or snapshots of two different people.

We asked him, Do the photographs depict the same person or not? Putting his nose close to each photo and gazing hard at the details, Arthur got fourteen out of sixteen trials correct.

We were now sure that Arthur had no problem in recognizing faces and telling them apart. But could his failure to produce a strong galvanic skin response to his parents be part of a more global disturbance in his emotional abilities? How could we be certain that the head injury had not also damaged his limbic system? Maybe he had no emotions, period.

This seemed improbable because throughout the months I spent with Arthur, he showed a full range of human emotions. He laughed at my jokes and offered his own funny stories in return. He expressed frustration, fear and anger, and on rare occasions I saw him cry. Whatever the situation, his emotions were appropriate. Arthur’s problem, then, was neither his ability to recognize faces nor his ability to experience emotions; what was lost was his ability to link the two.

So far so good, but why is the phenomenon specific to close relatives? Why not call the mailman an impostor, since his, too, is a familiar face?

It may be that when any normal person (including Arthur, prior to his accident) encounters someone who is emotionally very close to him — a parent, spouse or sibling — he expects an emotional “glow”, a warm fuzzy feeling, to arise even though it may sometimes be experienced only very dimly. The absence of this glow is therefore surprising and Arthur’s only recourse then is to generate an absurd delusion — to rationalize it or to explain it away. On the other hand, when one sees the mailman, one doesn’t expect a warm glow and consequently there is no incentive for Arthur to generate a delusion to explain his lack of “warm fuzzy” response. A mailman is simply a mailman (unless the relationship has taken an amorous turn).

Although the most common delusion among Capgras’ patients is the assertion that a parent is an impostor, even more bizarre examples can be found in the older medical literature. Indeed, in a case on record the patient was convinced that his stepfather was a robot, proceeded to decapitate him and opened his skull to look for microchips. Perhaps in this patient, the dissociation from emotions was so extreme that he was forced into an even more absurd delusion than Arthur’s: that his stepfather was not even a human being, but was a mindless android!4

About a year ago, when I gave a lecture on Arthur at the Veterans Administration Hospital in La Jolla, a neurology resident raised an astute objection to my theory. What about people who are born with a disease in which their amygdalas (the gateway to the limbic system) calcify and atrophy or those who lose their amygdalas (we each have two of them) completely in surgery or through an accident? Such people do exist, but they do not develop Capgras’ syndrome, even though their GSRs are flat to all emotionally evocative stimuli. Likewise, patients with damage to their frontal lobes (which receive and process information from the limbic system for making elaborate future plans) also often lack a GSR. Yet they, too, do not display Capgras’ syndrome.

Why not? The answer may be that these patients experience a general blunting of all their emotional responses and therefore do not have a baseline for comparison. Like a purebred Vulcan or Data on Star Trek, one could legitimately argue, they don’t even know what an emotion is, whereas Capgras’ patients like Arthur enjoy a normal emotional life in all other respects.

This idea teaches us an important principle about brain function, namely, that all our perceptions — indeed, maybe all aspects of our minds — are governed by comparisons and not by absolute values. This appears to be true whether you are talking about something as obvious as judging the brightness of print in a newspaper or something as subtle as detecting a blip in your internal emotional landscape. This is a far-reaching conclusion, and it also helps illustrate the power of our approach — indeed of the whole discipline that now goes by the name cognitive neuroscience. You can discover important general principles about how the brain works and begin to address deep philosophical questions by doing relatively simple experiments on the right patients. We started with a bizarre condition, proposed an outlandish theory, tested it in the lab and — in meeting objections to it — learned more about how the healthy brain actually works.

Taking these speculations even further, consider the extraordinary disorder called Cotard’s syndrome, in which a patient will assert that he is dead, claiming to smell rotten flesh or worms crawling all over his skin.

Again, most people, even neurologists, would jump to the conclusion that the patient was insane. But that wouldn’t explain why the delusion takes this highly specific form. I would argue instead that Cotard’s is simply an exaggerated form of Capgras’ syndrome and probably has a similar origin. In Capgras’, the face recognition area alone is disconnected from the amygdala, whereas in Cotard’s perhaps all the sensory areas are disconnected from the limbic system, leading to a complete lack of emotional contact with the world. Here is another instance in which an outlandish brain disorder that most people regard as a psychiatric problem can be explained in terms of known brain circuitry. And once again, these ideas can be tested in the laboratory. I would predict that Cotard’s syndrome patients will have a complete loss of GSR for all external stimuli — not just faces — and this leaves them stranded on an island of emotional desolation, as close as anyone can come to experiencing death.

Arthur seemed to enjoy his visits to our laboratory. His parents were pleased that there was a logical explanation for his predicament, that he wasn’t just “crazy”. I never revealed the details to Arthur because I wasn’t sure how he’d react.

Arthur’s father was an intelligent man, and at one point, when Arthur wasn’t around, he asked me, “If your theory is correct, doctor — if the information doesn’t get to his amygdala — then how do you explain how he has no problems recognizing us over the phone? Does that make sense to you?”

“Well”, I replied, “there is a separate pathway from the auditory cortex, the hearing area of the temporal lobes, to the amygdala. One possibility is that this hearing route has not been affected by the accident — only the visual centers have been disconnected from Arthur’s amygdala”.

This conversation got me wondering about the other well-known functions of the amygdala and the visual centers that project to it. In particular, scientists recording cell responses in the amygdala found that, in addition to responding to facial expression and emotions, the cells also respond to the direction of eye gaze.

For instance, one cell might fire if another person is looking directly at you, whereas a neighboring cell will fire only if that person’s gaze is averted by a fraction of an inch. Still other cells fire when the gaze is way off to the left or the right.

This phenomenon is not surprising, given the important role that gaze direction5 plays in primate social communications — the averted gaze of guilt, shame or embarrassment; the intense, direct gaze of a lover or the threatening stare of an enemy. We tend to forget that emotions, even though they are privately experienced, often involve interactions with other people and that one way we interact is through eye contact. Given the links among gaze direction, familiarity and emotions, I wondered whether Arthur’s ability to judge the direction of gaze, say, by looking at photographs of faces, would be impaired.

To find out, I prepared a series of images, each showing the same model looking either directly at the camera lens or at a point an inch or two to the right or left of the lens. Arthur’s task was simply to let us know whether the model was looking straight at him or not. Whereas you or I can detect tiny shifts in gaze with uncanny accuracy, Arthur was hopeless at the task. Only when the model’s eyes were looking way off to one side was he able to discern correctly that she wasn’t looking at him.

This finding in itself is interesting but not altogether unexpected, given the known role of amygdala and temporal lobes in detecting gaze direction. But on the eighth trial of looking at these photos, Arthur did something completely unexpected. In his soft, almost apologetic voice, he exclaimed that the model’s identity had changed. He was now looking at a new person!

This meant that a mere change in direction of gaze had been sufficient to provoke Capgras’ delusion. For Arthur, the “second” model was apparently a new person who merely resembled the “first”.

“This one is older”, Arthur said firmly. He stared hard at both images. “This is a lady; the other one is a girl.”

Later in the sequence, Arthur made another duplication — one model was old, one young and a third even younger. At the end of the test session he continued to insist that he had seen three different people. Two weeks later he did it again on a retest using images of a completely new face.

How could Arthur look at the face of what was obviously one person and claim that she was actually three different people? Why did simply changing the direction of gaze lead to this profound inability to link successive images?

Answers lie in the mechanics of how we form memories, in particular our ability to create enduring representations of faces. For example, suppose you go to the grocery store one day and a friend introduces you to a new person — Joe. You form a memory of that episode and tuck it away in your brain. Two weeks go by and you run into Joe in the library. He tells you a story about your mutual friend, you share a laugh and your brain files a memory about this second episode. Another few weeks pass and you meet Joe again in his office — he’s a medical researcher and he’s wearing a white lab coat — but you recognize him instantly from earlier encounters. More memories of Joe are created during this time so that you now have in your mind a “category” called Joe. This mental picture becomes progressively refined and enriched each time you meet Joe, aided by an increasing sense of familiarity that creates an incentive to link the images and the episodes.

Eventually you develop a robust concept of Joe — he tells great stories, works in a lab, makes you laugh, knows a lot about gardening, and so forth.

Now consider what happens to someone with a rare and specific form of amnesia, caused by damage to the hippocampus (another important brain structure in the temporal lobes). These patients have a complete inability to form new memories, even though they have perfect recollection of all events in their lives that took place before the hippocampus was injured. The logical conclusion to be drawn from the syndrome is not that memories are actually stored in the hippocampus (hence the preservation of old memories), but that the hippocampus is vital for the acquisition of new memory traces in the brain. When such a patient meets a new person (Joe) on three consecutive occasions — in the supermarket, the library and the office — he will not remember ever having met Joe before. He will simply not recognize him. He will insist each time that Joe is a complete stranger, no matter how many times they have interacted, talked, exchanged stories and so forth.

But is Joe really a complete stranger? Rather surprisingly, experiments show that such amnesia patients actually retain the ability to form new categories that transcend successive Joe episodes. If our patient met Joe ten times and each time Joe made him laugh, he’d tend to feel vaguely jovial or happy on the next encounter but still would not know who Joe is. There would be no sense of familiarity whatsoever — no memory of each Joe episode — and yet the patient would acknowledge that Joe makes him happy. This means that the amnesia patient, unlike Arthur, can link successive episodes to create a new concept (an unconscious expectation of joy) even though he forgets each episode, whereas Arthur remembers each episode but fails to link them.

Thus Arthur is in some respects the mirror image of our amnesia patient. When he meets a total stranger like Joe, his brain creates a file for Joe and the associated experiences he has with Joe. But if Joe leaves the room for thirty minutes and returns, Arthur’s brain — instead of retrieving the old file and adding to it — sometimes creates a completely new one.

Why does this happen in Capgras’ syndrome? It may be that to link successive episodes the brain relies on signals from the limbic system — the “glow” or sense of familiarity associated with a known face and set of memories — and if this activation is missing, the brain cannot form an enduring category through time. In the absence of this glow, the brain simply sets up separate categories each time; that is why Arthur asserts that he is meeting a new person who simply resembles the person he met thirty minutes ago. Cognitive psychologists and philosophers often make a distinction between tokens and types — that all our experiences can be classified into general categories or tokens (people or cars) versus specific exemplars or types (Joe or my car).

Our experiments with Arthur suggest that this distinction is not merely academic; it is embedded deep in the architecture of the brain.

As we continued testing Arthur, we noticed that he had certain other quirks and eccentricities. For instance, Arthur sometimes seemed to have a general problem with visual categories. All of us make mental taxonomies or groupings of events and objects: Ducks and geese are birds but rabbits are not. Our brains set up these categories even without formal education in zoology, presumably to facilitate memory storage and to enhance our ability to access these memories at a moment’s notice.

Arthur, on the other hand, often made remarks hinting that he was confused about categories. For example, he had an almost obsessive preoccupation with Jews and Catholics, and he tended to label a disproportionate number of recently encountered people as Jews. This propensity reminded me of another rare syndrome called Fregoli, in which a patient keeps seeing the same person everywhere. In walking down the street, nearly every woman’s face might look like his mother’s or every young man might resemble his brother. (I would predict that instead of having severed connections from face recognition areas to the amygdala, the Fregoli patient may have an excess of such connections. Every face would be imbued with familiarity and “glow”, causing him to see the same face over and over again.) Might such Fregoli-like confusion occur in otherwise normal brains? Could this be a basis for forming racist stereotypes? Racism is so often directed at a single physical type (Blacks, Asians, Whites and so forth).

Perhaps a single unpleasant episode with one member of a visual category sets up a limbic connection that is inappropriately generalized to include all members of that class and is notoriously impervious to “intellectual correction” based on information stored in higher brain centers. Indeed one’s intellectual views may be colored (no pun intended) by this emotional knee-jerk reaction; hence the notorious tenacity of racism.

•

We began our journey with Arthur trying to explain his strange delusions about impostors and uncovered some new insights into how memories are stored and retrieved in the human brain. His story offers insights into how each of us constructs narratives about our life and the people who inhabit it. In a sense your life — your autobiography — is a long sequence of highly personal episodic memories about your first kiss, prom night, wedding, birth of a child, fishing trips and so on. But it is also much more than that. Clearly, there is a personal identity, a sense of a unified “self” that runs like a golden thread through the whole fabric of our existence. The Scottish philosopher David Hume drew an analogy between the human personality and a river — the water in the river is ever-changing and yet the river itself remains constant. What would happen, he asked, if a person were to dip his foot into a river and then dip it in again after half an hour — would it be the same river or a different one? If you think this is a silly semantic riddle, you’re right, for the answer depends on your definition of “same” and “river”. But silly or not, one point is clear. For Arthur, given his difficulty with linking successive episodic memories, there may indeed be two rivers! To be sure, this tendency to make copies of events and objects was most pronounced when he encountered faces — Arthur did not often duplicate objects. Yet there were occasions when he would run his fingers through his hair and call it a “wig”, partly because his scalp felt unfamiliar as a result of scars from the neurosurgery he had undergone. On rare occasions, Arthur even duplicated countries, claiming at one point that there were two Panamas (he had recently visited that country during a family reunion).

Most remarkable of all, Arthur sometimes duplicated himself! The first time this happened, I was showing Arthur pictures of himself from a family photo album and I pointed to a snapshot of him taken two years before the accident.

“Whose picture is this?” I asked.

“That’s another Arthur”, he replied. “He looks just like me but it isn’t me.” I couldn’t believe my ears. Arthur may have detected my surprise since he then reinforced his point by saying, “You see? He has a mustache. I don’t.”

This delusion, however, did not occur when Arthur looked at himself in a mirror. Perhaps he was sensible enough to realize that the face in the mirror could not be anyone else’s. But Arthur’s tendency to “duplicate” himself — to regard himself as a distinct person from a former Arthur — also sometimes emerged spontaneously during conversation. To my surprise, he once volunteered, “Yes, my parents sent a check, but they sent it to the other Arthur.”

Arthur’s most serious problem, however, was his inability to make emotional contact with people who matter to him most — his parents — and this caused him great anguish. I can imagine a voice inside his head saying, “The reason I don’t experience warmth must be because I’m not the real Arthur.” One day Arthur turned to his mother and said, “Mom, if the real Arthur ever returns, do you promise that you will still treat me as a friend and love me?” How can a sane human being who is perfectly intelligent in other respects come to regard himself as two people? There seems to be something inherently contradictory about splitting the Self, which by its very nature is unitary. If I started to regard myself as several people, which one would I plan for? Which one is the “real” me? This is a real and painful dilemma for Arthur.

Philosophers have argued for centuries that if there is any one thing about our existence that is completely beyond question, it is the simple fact that “I” exist as a single human being who endures in space and time. But even this basic axiomatic foundation of human existence is called into question by Arthur.

| <<< Íàçàä CHAPTER 7 The Sound of One Hand Clapping |

Âïåðåä >>> CHAPTER 9 God and the Limbic System |

- Foreword

- Preface

- CHAPTER 1 The Phantom Within

- CHAPTER 2 “Knowing Where to Scratch”

- CHAPTER 3 Chasing the Phantom

- CHAPTER 4 The Zombie in the Brain

- CHAPTER 5 The Secret Life of James Thurber

- CHAPTER 6 Through the Looking Glass

- CHAPTER 7 The Sound of One Hand Clapping

- CHAPTER 8 “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”

- CHAPTER 9 God and the Limbic System

- CHAPTER 10 The Woman Who Died Laughing

- CHAPTER 11 “You Forgot to Deliver the Twin”

- CHAPTER 12 Do Martians See Red?

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography and Suggested Reading

- Index

- Ñîäåðæàíèå êíèãè

- Ïîïóëÿðíûå ñòðàíèöû

- CHAPTER 8 “The Unbearable Lightness of Being”

- “They Had No Choice”

- CHAPTER 2 “Knowing Where to Scratch”

- CHAPTER 1 The Phantom Within

- CHAPTER 7 The Sound of One Hand Clapping

- CHAPTER 4 The Zombie in the Brain

- CHAPTER 9 God and the Limbic System

- CHAPTER 12 Do Martians See Red?

- CHAPTER 6 Through the Looking Glass

- CHAPTER 3 Chasing the Phantom

- CHAPTER 5 The Secret Life of James Thurber

- CHAPTER 10 The Woman Who Died Laughing